![]()

After your first draft, let your manuscript breathe for a week or so then properly assess your work. You need to know where you truly are to determine where you should be going. Build your map.

The first draft is often the fun part. The rules are so fluid. You change your character from Sarah to Karo mid-paragraph because you’ve noticed that everyone else in the spaceship also has a name that begins with S. Then, after another chapter or two, you make the spaceship a submarine. You try out a flashback and fall in love with that world. That’s the novel now. Forget the submarine, the whole thing is set on a pig farm in Lithuania. And, some time later, you come out the other end with… what? A manuscript full of the problems that past you left for future you to clean up.

Now, there’s good news and there’s bad news. The bad news is, you’re future you, so you’ve got work to do. The good news is, you get a chance to make this thing good. You get to fix the drifting names and the undercooked settings, the top-heavy structure. You get to go back in and plant clues and images, to focus the theme.

So, where to start? First off, do nothing. Let the whole thing brew so that when you return you’ll have some objectivity. Give it a couple of weeks.

Almost by definition, a novel is long. In its details, all its scenes and characters and images — let alone sentences, it probably won’t all fit in your head at once. Your first task, then, is to build a map of what you’ve got so you can decide how you need to change it.

Read through your draft, and make very brief notes as you read. While you should bear in mind changes that you want to make, try to reflect what you read rather than the better draft you will produce.

Here are some of the aspects of your draft you should consider capturing.

Scenes and more

A brief list of scenes in the chapter. For extra points, also note significant summary passages. If you are running multiple narratives, it may be worth noting which scene belongs to which narrative.

Flashbacks

Back to the Lithuanian Pig farm. Later on, you’ll want to gauge the balance of present action to back story.

Subplots

Track those parts of the story that support, mirror, or counterpoint the main narrative. Think about threads that might be cut, slimmed or strengthened.

Theme/Premise

What is the mood of the chapter? What is it saying? Can you declare it’s about-ness in a word? Can you boil the action down to a premise of the Love Conquers All variety? In the dark SF detective novel I’m writing, I ended up with cheerful conclusions such as everyone is in exile and no-one is safe.

Image

Are you using motifs or images in the chapter? Is there a colour palette? Do objects of symbolic importance appear?

Setting

List locations in the chapter. Also make a note of any elements related to your world building — the politics, geography, seasons, weather.

Characters

Keep a running tally of your characters. Ignore walk-on parts, unless they play a key glancing role in the narrative. Keep an eye open for drifting names.

Notes

Time for some constructive criticism. What did you think of the chapter? What worked? what failed? How should you change things? Although, in other sections, the object of the exercise is to capture the state of your manuscript as it stands, this is your chance to think about the next draft. What you should you cut, what you should add.

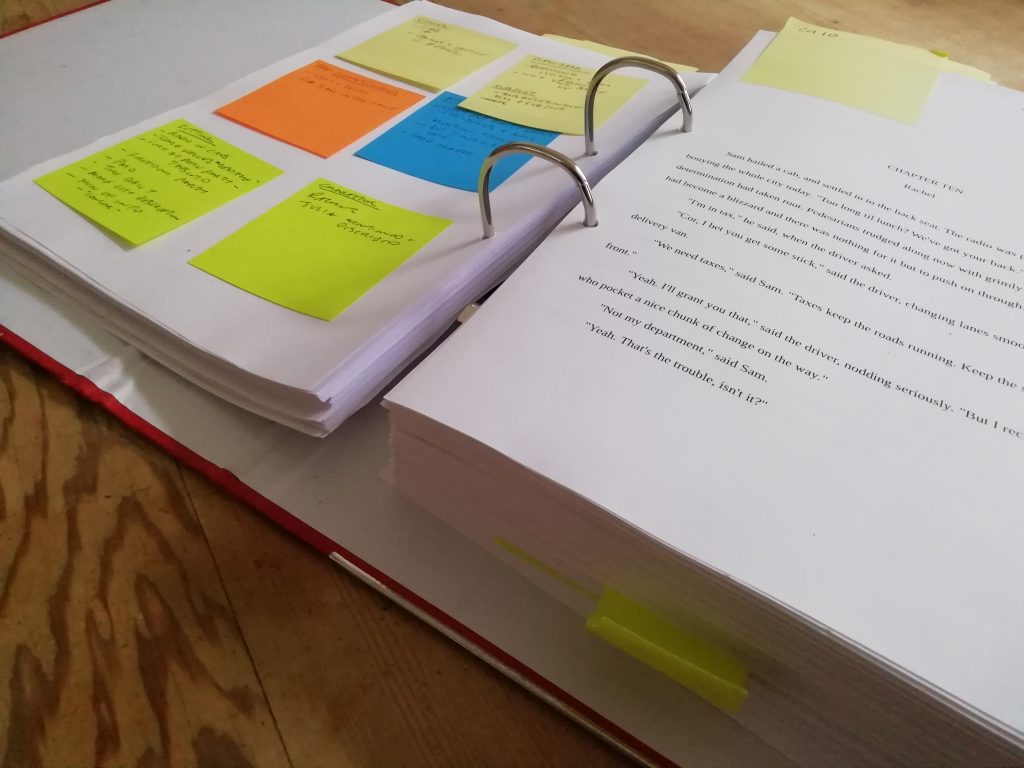

There are many ways to capture this information. For a rewarding tactile experience, you can stick Post-It notes into your printout. It is nice to get back to paper and there’s a real feeling of satisfaction as you literally turn the page on a chapter.

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">The draft mapped with Post-It notes</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">The draft mapped with Post-It notes</figcaption></figure>

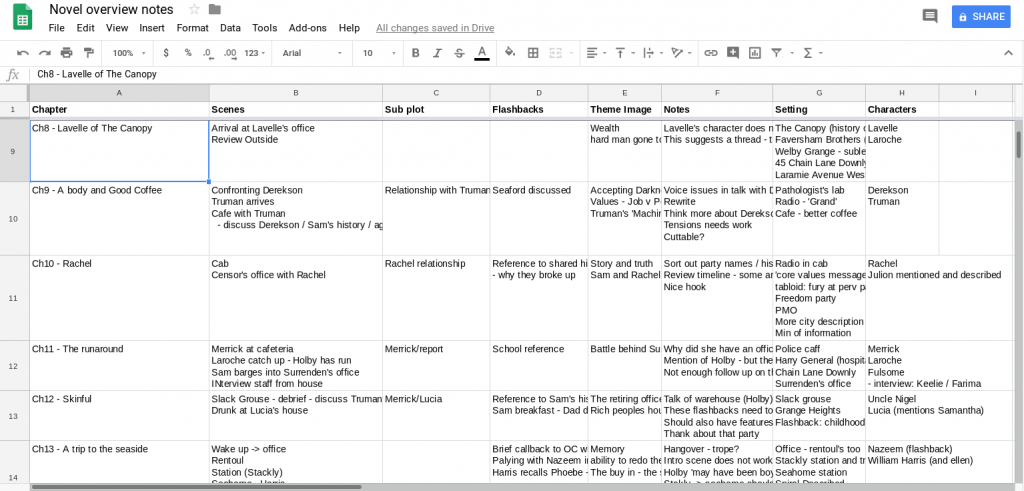

It’s less pleasurable but arguably more useful to use a spreadsheet, though. That way, you can see all your notes in one place and follow a column without having to leaf back through five hundred pages. As you can see from these snaps, I took both approaches when assessing my draft. Next time round, I’ll probably save myself the transcription and type straight into the document.

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">The map in spreadsheet form</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">The map in spreadsheet form</figcaption></figure>

By tracking the character column I can get a sense of who is who, whether any characters need further development, I can catch names that tend to drift (I have a particular issue with one character who seems to have three interchangeable names) and so on. When I think about structure, I can trace all the scenes, the balance between present action and flashback, the points at which subplots intersect with the main plot. And I have all my hypercritical notes to hand, too.

Armed with this master map we’re ready to begin to plan for our next draft… but that’s another story.